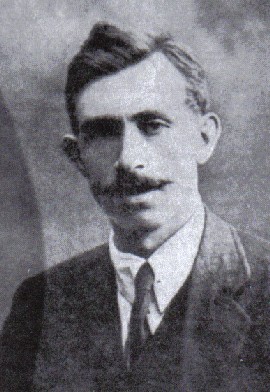

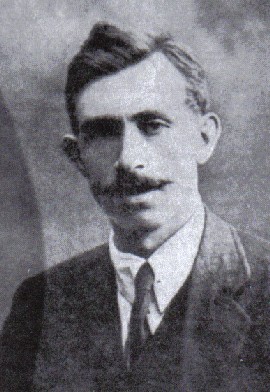

Donncadh O’Hannigan, OC East Limerick Flying Columns.

CAHERGUILLAMORE

THE PRELUDE TO DROMKEEN

The events of Saint Stephen’s night of 1920 left a lasting impression on the

people of East Limerick, both those involved and those who heard of them. In

fact it proved to be a night never to be forgotten by those who were there. It

was customary in those times to have house dances, a form of entertainment that

was widespread throughout rural Ireland. After the four weeks of Advent, a

season of preparation for the feast of Christmas, when of course dancing was not

allowed, the young men and women were looking forward to a night of

entertainment. But then 1920 was not a normal year and the times were very

troubled. The War of Independence in East Limerick had been gaining momentum for

months previously, and young men from every parish and townland were ‘on the

run’, while the RIC garrisons in every town and village had been recently

reinforced with additional MC, Black and Tans or regular British troops. Members

of the various active volunteer service units took the opportunity to visit

home, or relatives, always done swiftly by night and always of short duration.

Word was spread by word of mouth that a dance was to be held in Herbertstown.

The news travelled swiftly from farmhouse to cottage around the town of Bruff in

East Limerick. The rumour was a decoy. The dance was to be held, not in

Herbertstown, but in Caherguillamore House, the mansion of the Viscounts

O’Grady, relatives of Lord Fermoy. The reigning Viscount had left

Caherguillamore for warmer climes, far from the troubled countryside of East

Limerick, where the forces of the British crown were carrying on a reign of

terror on the local inhabitants involving murder, burnings, interrogation and

constant harassment. Caherguillamore mansion had been selected for the dance by

members of the Bruff Battalion of Volunteers and the function was being held to

raise funds for the purchase of arms to equip the Battalion Flying Column. So

having spread the rumour that Herbertstown was the venue, the organisers went

ahead with their programme and expected more than three hundred guests to

attend. As the admission charge was high, four shillings, a free supper was to

be given for the dancers and to this end a number of sheep were obtained and

slaughtered, and all the catering arrangements made. Slaughter is the word that

describes what subsequently transpired.

Inside the house the dance went on, oblivious of the hundreds of British troops,

RIC and Black and Tans who were just then closing in on foot along the roadways

and laneways leading from Limerick city towards Bruff. Despite all precautions,

the British had got word that most of the much-wanted Volunteer leaders and

Column members would be in Caherguillamore that night.

Suddenly, near midnight the stillness was shattered by volleys of rifle fire. A

hail of bullets thudded into the walls of the mansion, and poured through

shutters and windows. The sounds of breaking glass, Verey lights and volley

after volley of rifle fire from the unseen military, police and Tans who had the

house surrounded. Inside the ballroom mass hysteria reigned as volley after

volley of rifle fire poured in through the windows. The attackers burst through

the front and rear doors, and even the windows, and with fixed bayonets and

clubbing rifle butts charged in on the 150 young men and 90 young girls running

for safety through the house. What happened next can hardly be told in words.

Brutality ran rampant. Many of the boys at the dance had no connection with the

volunteers at all. Some were savagely stabbed with bayonets intended for trench

warfare; others were clubbed with rifle butts upon the face and head, and then

kicked repeatedly while lying on the floor. The girls were herded upstairs and

searched by women searchers brought from Limerick for that purpose. The

Commander of the attacking force, Colonel Wilkinson decided to carry out

“interrogations” in the ballroom for the purpose of identifying volunteer

leaders or others “on the run”. Each man was ordered to proceed in turn from the

kitchen to the ballroom, running a gauntlet of two long lines of RIC, Black and

Tans, and regular military. As he went through the lines of green-blue, khaki

and black he was beaten on the head, body and limbs with rifle butts from the

front by those troops on his left and from behind by those on the right. If they

fell, they were kicked into rising and forced to stagger on. One young man spat

out most of his teeth broken by a rifle butt, and stumbled on to where Colonel

Wilkinson and his officers were conducting the investigation. This was James

Moloney, later Commandant of the Bruff Battalion. In the initial stages of the

attack, some Black and Tans had engaged in fire with the sentries who returned

the fire. In this exchange one of the Tans were killed, a Constable Alfred C.

Hogsden of London. The death of one of their number drove the Tans insane. They

smashed the banisters of the stairs and laid into the defenceless and already

badly-injured men using the timber to bludgeon and club the men cornered in the

corridors and passages. All through the night the girls imprisoned upstairs

heard the rampage of terror going on, and not until loam the next morning were

they released. They had spent the night praying as they listened to the cursing,

swearing and beatings in the rooms below. The dead volunteers were thrown on a

lorry and taken to Limerick, while the others, blood-smeared and unbandaged were

loaded into lorries and taken in convoy to Limerick where they were imprisoned

in Sarsfield Barracks, then known as New Barracks. The people of Limerick who

witnessed the awful scenes, never forgot the sight of those vehicles carrying

over one hundred blood-stained and suffering young men.

Military, RIC and Black and Tans from Limerick city, Bruff, Fedamore, Croom and

Pallasgreen took part on that night. Five volunteers were killed that night.

They were later interred in the Republican Plot at Limerick. At the New Barracks

the prisoners spent the night of December 27th lying on the floor of an old

church into which they had been beaten on arrival. The following morning they

were taken to the barrack yard and subjected to further “interrogation” this

time in the presence of RIC from rural areas who had been brought in to assist

in identifying wanted men. Subsequently all the prisoners were transferred to

Limerick jail, court-martialled before a tribunal. Many were given sentences of

ten years imprisonment and sent to prisons in Portsmouth and Dartmoor. Others

got lighter sentences and sent to the convict prison and British military post

on Spike Island. No wonder then, that in January 1921 a conspicuous flag in the

colours of

Black and Tan, floated high above the large Barracks in Pallasgreen. It of

course identified the police barracks, but it was also a symbol intended to

strike fear into the populace of East Limerick. Pallas was the headquarters of a

Police District, in the charge of an officer who was a District Inspector, but

whose special task, and that of the large garrison was indicated by the flag,

which was to strike terror into the hearts and minds of the inhabitants of the

surrounding countryside. A challenge it indeed was; a challenge indeed which was

firmly met and answered one month later at Dromkeen.

(Taken from “Limerick’s Fighting Story” by Colonel J.M. MacCarthy.)

Donncadh O’Hannigan, OC East Limerick Flying Columns.